Overview

We perform interdisciplinary research at the interface of chemistry and materials science. In order to improve the function and properties of materials, we strive to understand them fundamentally via the tools of synthetic organic chemists. If you are a chemistry or biochemistry major who wants to apply knowledge from your coursework towards studying materials, or if you are a materials engineering major who would like to develop your chemical intuition, this may be the research experience for you!

We are seeking students who work well with others, who will ask a lot of questions to deepen your understanding, and who have interest in the subject matter. Students are involved in every aspect of our research projects, including designing experiments, analyzing data, and communicating results through publications and presentations.

Interested students should read the following research introduction for new students and email Dr. Hamachi with their resume to inquire about available projects.

Research Introduction for New Students

Topics

1. Colloidal Nanoparticle Synthesis

2. Covalent Organic Frameworks

Colloidal Nanoparticle Synthesis

|

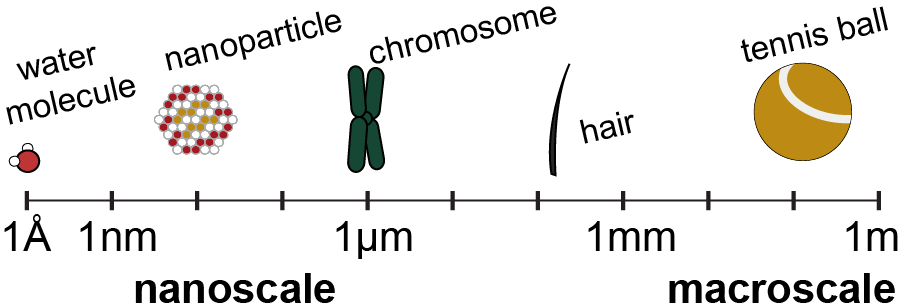

How small is a nanometer? If you were to take the diameter of a human hair and split it in half twenty times, that would be approximately the size of a nanometer. Scientists are interested in nanoparticles because at those small length scales, new properties can emerge. One example is gold nanoparticles at the nanoscale which range in color from red, to purple, to blue, based on their shape and size. Another example is the cadmium selenide nanoparticles that Dr. Hamachi studied during her Ph.D. which glow a rainbow of colors from red to blue based on the particle diameter. |

|

|

In the Hamachi Group, we are interested in nanoparticle synthesis and characterization. For many applications, it is important to consistently make a narrow size distribution of nanoparticles. We seek to develop new synthetic methods to achieve this. This research involves a mixture of organic chemistry techniques (1H NMR, FTIR), physical chemistry techniques (DLS, Fluorescence Spectroscopy) and materials engineering techniques (PXRD, SEM). You do not need prior experience with these techniques to be able to participate in a research project, although it is suggested that you have taken the first two quarters of gen chem. |

For more background information on characterizing nanomaterials with X-ray diffraction and nanoparticle crystallization, you can read these articles from prominent research groups in the field. Please note that you may need to be on the campus wireless network in order to access them:

1. Tutorial on Powder X-ray Diffraction for Characterizing Nanoscale Materials

2. Crystallization by Particle Attachment in Synthetic, Biogenic, and Geologic Environments

Covalent Organic Frameworks

|

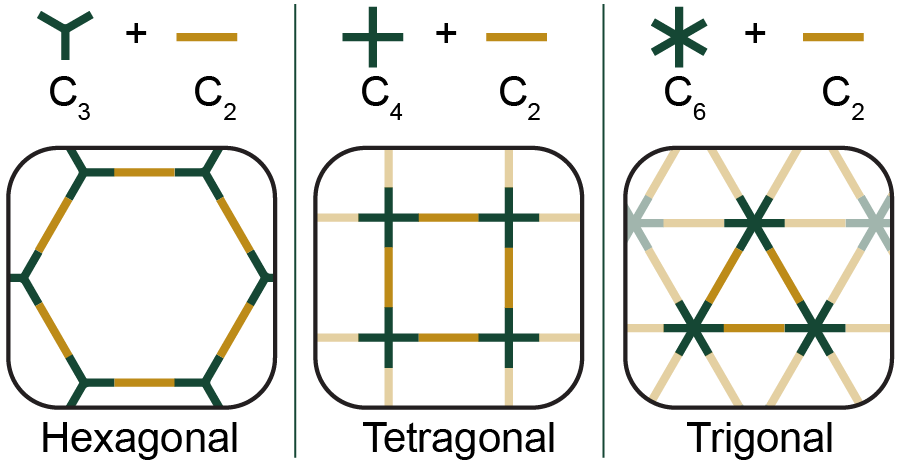

Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) are a class of crystalline, porous polymers synthesized from well-defined molecular building blocks called monomers. You can imagine this class of materials as molecular sponges where each hole in the sponge is the same size, and can be modified to absorb specific pollutants. By swapping out the monomers for ones of different shapes and sizes, we can change the structure of the crystal as well as the size and shape of the pores. COFs are very high surface area materials that can adsorb gasses/analytes and to be used in molecular separations. |

|

|

In the Hamachi Group, we are interested in developing methods to synthesize colloidal COFs. Here is a recent publication from the group on synthesizing colloidal COF-300. This research involves a mixture of organic chemistry techniques (1H NMR, GC/MS, FTIR), physical chemistry techniques (DLS, surface area analysis), and materials engineering techniques (PXRD, SEM). You do not need prior experience with these techniques to be able to participate in a research project, although it is suggested that you have taken the first two quarters of gen chem. |

For more background information on this topic, you can read these articles from a few prominent research groups in the field. Please note that you may need to be on the campus wireless network in order to access them:

1. Covalent Organic Frameworks as a Platform for Multidimensional Polymerization

2. Covalent Organic Frameworks: Chemical Approaches to Designer Structures and Built-In Functions